Modeling ragged time-varying hierarchies

This article covers an approach to handling time-varying ragged hierarchies in a

To help visualize this data, we’re going to pretend we are a company that manufactures and rents out eBikes in a ride share application. When we build a bike, we keep track of the serial numbers of the components that make up the bike. Any time something breaks and needs to be replaced, we track the old parts that were removed and the new parts that were installed. We also precisely track the mileage accumulated on each of our bikes. Our primary analytical goal is to be able to report on the expected lifetime of each component, so we can prioritize improving that component and reduce costly maintenance.

Note: this article originally published on the dbt developer blog.

Data model

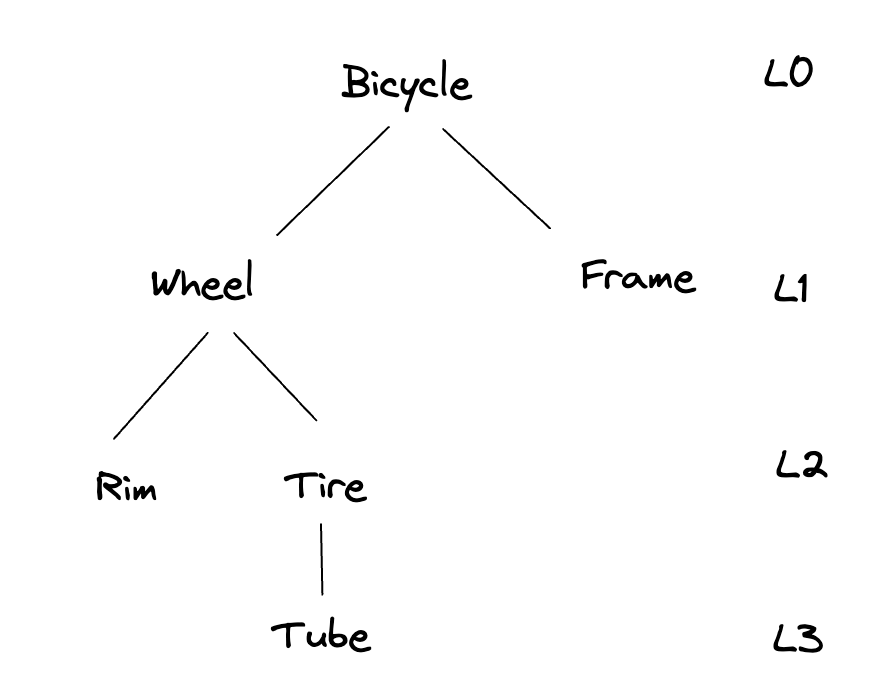

Obviously, a real bike could have a hundred or more separate components. To keep things simple for this article, let’s just consider the bike, the frame, a wheel, the wheel rim, tire, and tube. Our component hierarchy looks like:

This hierarchy is ragged because different paths through the hierarchy terminate at different depths. It is time-varying because specific components can be added and removed.

Now let’s take a look at how this data is represented in our source data systems and how it can be transformed to make analytics queries easier.

Transactional model

Our ERP system (Enterprise Resource Planning) contains records that log when a specific component serial number (component_id) was installed in or removed from a parent assembly component (assembly_id). The top-most assembly component is the eBike itself, which has no parent assembly. So when an eBike (specifically, the eBike with serial number “Bike-1”) is originally constructed, the ERP system would contain records that look like the following.

erp_components:

assembly_id |

component_id |

installed_at |

removed_at |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bike-1 | 2023-01-01 | ||

| Bike-1 | Frame-1 | 2023-01-01 | |

| Bike-1 | Wheel-1 | 2023-01-01 | |

| Wheel-1 | Rim-1 | 2023-01-01 | |

| Wheel-1 | Tire-1 | 2023-01-01 | |

| Tire-1 | Tube-1 | 2023-01-01 |

Now let’s suppose this bike has been ridden for a while, and on June 1, the user of the bike reported a flat tire. A service technician then went to the site, replaced the tube that was in the wheel, and installed a new one. They logged this in the ERP system, causing one record to be updated with a removed_at date, and another record to be created with the new tube component_id.

erp_components:

assembly_id |

component_id |

installed_at |

removed_at |

|---|---|---|---|

| … | … | … | … |

| Tire-1 | Tube-1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-06-01 |

| Tire-1 | Tube-2 | 2023-06-01 | |

| … | … | … | … |

After a few more months, there is a small crash. Don’t worry, everyone’s OK! However, the wheel (Wheel-1)is totally broken and must be replaced (with Wheel-2). When the technician updates the ERP, the entire hierarchy under the replaced wheel is also updated, as shown below.

erp_components:

assembly_id |

component_id |

installed_at |

removed_at |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bike-1 | Wheel-1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-08-01 | |

| Wheel-1 | Rim-1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-08-01 | |

| Wheel-1 | Tire-1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-08-01 | |

| Tire-1 | Tube-2 | 2023-06-01 | 2023-08-01 | # Note that this part has different install date |

| Bike-1 | Wheel-2 | 2023-08-01 | ||

| Wheel-2 | Rim-2 | 2023-08-01 | ||

| Wheel-2 | Tire-2 | 2023-08-01 | ||

| Tire-2 | Tube-3 | 2023-08-01 |

After all of the above updates and additions, our ERP data looks like the following.

erp_components:

assembly_id |

component_id |

installed_at |

removed_at |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bike-1 | 2023-01-01 | ||

| Bike-1 | Frame-1 | 2023-01-01 | |

| Bike-1 | Wheel-1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-08-01 |

| Wheel-1 | Rim-1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-08-01 |

| Wheel-1 | Tire-1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-08-01 |

| Tire-1 | Tube-1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-06-01 |

| Tire-1 | Tube-2 | 2023-06-01 | 2023-08-01 |

| Bike-1 | Wheel-2 | 2023-08-01 | |

| Wheel-2 | Rim-2 | 2023-08-01 | |

| Wheel-2 | Tire-2 | 2023-08-01 | |

| Tire-2 | Tube-3 | 2023-08-01 |

So that’s all fine and good from the perspective of the ERP system. But this data structure can be difficult to work with if we want to generate reports that calculate the total mileage accumulated on various components, or the average mileage of a particular component type, or how one component type might affect the lifetime of another component.

Multivalued dimensional model

In dimensional modeling, we have fact tables that contain measurements and dimension tables that contain the context for those measurements (attributes). In our eBike data warehouse, we have a fact table that contains one record for each eBike for each day it is ridden and the measured mileage accumulated during rides that day. This fact table contains surrogate key columns, indicated by the _sk suffix. These are usually system-generated keys used to join to other tables in the database; the specific values of these keys are not important.

fct_daily_mileage:

bike_sk |

component_sk |

ride_at |

miles |

|---|---|---|---|

| bsk1 | csk1 | 2023-01-01 | 3 |

| bsk1 | csk1 | 2023-01-02 | 2 |

| bsk1 | csk1 | 2023-01-03 | 0 |

| bsk1 | csk1 | 2023-01-04 | 0 |

| … | … | … | … |

| bsk1 | csk3 | 2023-08-01 | 7 |

| bsk1 | csk3 | 2023-08-02 | 8 |

| bsk1 | csk3 | 2023-08-03 | 4 |

One of the dimension tables is a simple table containing information about the individual bikes we have manufactured.

dim_bikes:

bike_sk |

bike_id |

color |

model_name |

|---|---|---|---|

| bsk1 | Bike-1 | Orange | Wyld Stallyn |

There is a simple many-to-one relationship between fct_daily_mileage and dim_bikes. If we need to calculate the total mileage accumulated for each bike in our entire fleet of eBikes, we just join the two tables and aggregate on the miles measurement.

select

dim_bikes.bike_id,

sum(fct_daily_mileage.miles) as miles

from

fct_daily_mileage

inner join

dim_bikes

on

fct_daily_mileage.bike_sk = dim_bikes.bike_sk

group by

1

Extending this to determine if orange bikes get more use than red bikes or whether certain models are preferred are similarly straightforward queries.

Dealing with all of the components is more complicated because there are many components installed on the same day. The relationship between days when the bikes are ridden and the components is thus multivalued. In dim_bikes, there is one record per bike and surrogate key. In our components dimension will have multiple records with the same surrogate key and will therefore be a multivalued dimension. Of course, to make things even more complicated, the components can change from day to day. To construct the multivalued dimension table, we break down the time-varying component hierarchy into distinct ranges of time where all of the components in a particular bike remain constant. At specific points in time where the components are changed, a new surrogate key is created. The final dimension table for our example above looks like the following, where the valid_from_at and valid_to_at represent the begin and end of a range of time where all the components of an eBike remain unchanged.

mdim_components:

component_sk |

assembly_id |

component_id |

depth |

installed_at |

removed_at |

valid_from_at |

valid_to_at |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| csk1 | Bike-1 | 0 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-06-01 | ||

| csk1 | Bike-1 | Frame-1 | 1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-06-01 | |

| csk1 | Bike-1 | Wheel-1 | 1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-08-01 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-06-01 |

| csk1 | Wheel-1 | Rim-1 | 2 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-08-01 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-06-01 |

| csk1 | Wheel-1 | Tire-1 | 2 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-08-01 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-06-01 |

| csk1 | Tire-1 | Tube-1 | 3 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-06-01 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-06-01 |

| csk2 | Bike-1 | 0 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-06-01 | 2023-08-01 | ||

| csk2 | Bike-1 | Frame-1 | 1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-06-01 | 2023-08-01 | |

| csk2 | Bike-1 | Wheel-1 | 1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-08-01 | 2023-06-01 | 2023-08-01 |

| csk2 | Wheel-1 | Rim-1 | 2 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-08-01 | 2023-06-01 | 2023-08-01 |

| csk2 | Wheel-1 | Tire-1 | 2 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-08-01 | 2023-06-01 | 2023-08-01 |

| csk2 | Tire-1 | Tube-2 | 3 | 2023-06-01 | 2023-08-01 | 2023-06-01 | 2023-08-01 |

| csk3 | Bike-1 | 0 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-08-01 | |||

| csk3 | Bike-1 | Frame-1 | 1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-08-01 | ||

| csk3 | Bike-1 | Wheel-2 | 1 | 2023-08-01 | 2023-08-01 | ||

| csk3 | Wheel-2 | Rim-2 | 2 | 2023-08-01 | 2023-08-01 | ||

| csk3 | Wheel-2 | Tire-2 | 2 | 2023-08-01 | 2023-08-01 | ||

| csk3 | Tire-2 | Tube-3 | 3 | 2023-08-01 | 2023-08-01 |

Now, let’s look at how this structure can help in writing queries. In a later section of this article, we’ll examine the SQL code that can take our ERP table and convert it into this dimensional model.

Mileage for a component

Suppose we wanted to know the total mileage accumulated on “Wheel-1”. The SQL code for determining this is very similar to that for determining the mileage for a given bike.

select

mdim_components.component_id,

sum(fct_daily_mileage.miles) as miles

from

fct_daily_mileage

inner join

mdim_components

on

fct_daily_mileage.component_sk = mdim_components.component_sk

group by

1

where

component_id = 'Wheel-1'

:::caution

One thing to be very cautious about when working with multivalued dimensions is that you need to be careful interpreting aggregations. For example, suppose we chose to aggregate on top_assembly_id (to reduce clutter, this field is not shown in the data model above because it is just “Bike-1” for each record). For this aggregation, we would be over-counting the total mileage on that top assembly because the join would result in a Cartesian product and thus we’d get a “fan-out” situation.

:::

Bonus: Finding components installed at the same time as other components

This structure simplifies other kinds of interesting analysis. Suppose we wanted to start exploring how one component affects another, like whether certain brands of tube needed to be replaced more often if they were in a new brand of tire. We can do this by partitioning the data into the segments of time where the components are not changing and looking for other components installed at the same time. For example, to find all of the components that were ever installed at the same time “Tube-3” was installed, we can collect them with a simple window function. We could then use the results of this query in a regression or other type of statistical analysis.

select distinct

component_id

from

mdim_components

qualify

sum(iff(component_id = 'Tube-3', 1, 0)) over (partition by valid_from_at, valid_to_at) > 0

SQL code to build the dimensional model

Now we get to the fun part! This section shows how to take the ERP source data and turn it into the multivalued dimensional model. This SQL code was written and tested using Snowflake, but should be adaptable to other dialects.

Traversing the hierarchy

The first step will be to traverse the hierarchy of components to find all components that belong to the same top assembly. In our example above, we only had one bike and thus just one top assembly; in a real system, there will be many (and we may even swap components between different top assemblies!).

The key here is to use a recursive join to move from the top of the hierarchy to all children and grandchildren. The top of the hierarchy is easy to identify because they are the only records without any parents.

with recursive

-- Contains our source data with records that link a child to a parent

components as (

select

*,

-- Valid dates start as installed/removed, but may be modified as we traverse the hierarchy below

installed_at as valid_from_at,

removed_at as valid_to_at

from

erp_components

),

-- Get all the source records that are at the top of hierarchy

top_assemblies as (

select * from components where assembly_id is null

),

-- This is where the recursion happens that traverses the hierarchy

traversal as (

-- Start at the top of hierarchy

select

-- Keep track of the depth as we traverse down

0 as component_hierarchy_depth,

-- Flag to determine if we've entered a circular relationship

false as is_circular,

-- Define an array that will keep track of all of the ancestors of a component

[component_id] as component_trace,

-- At the top of the hierarchy, the component is the top assembly

component_id as top_assembly_id,

assembly_id,

component_id,

installed_at,

removed_at,

valid_from_at,

valid_to_at

from

top_assemblies

union all

-- Join the current layer of the hierarchy with the next layer down by linking

-- the current component id to the assembly id of the child

select

traversal.component_hierarchy_depth + 1 as component_hierarchy_depth,

-- Check for any circular dependencies

array_contains(components.component_id::variant, traversal.component_trace) as is_circular,

-- Append trace array

array_append(traversal.component_trace, components.component_id) as component_trace,

-- Keep track of the top of the assembly

traversal.top_assembly_id,

components.assembly_id,

components.component_id,

components.installed_at,

components.removed_at,

-- As we recurse down the hierarchy, only want to consider time ranges where both

-- parent and child are installed; so choose the latest "from" timestamp and the earliest "to".

greatest(traversal.valid_from_at, components.valid_from_at) as valid_from_at,

least(traversal.valid_to_at, components.valid_to_at) as valid_to_at

from

traversal

inner join

components

on

traversal.component_id = components.assembly_id

and

-- Exclude component assemblies that weren't installed at the same time

-- This may happen due to source data quality issues

(

traversal.valid_from_at < components.valid_to_at

and

traversal.valid_to_at >= components.valid_from_at

)

where

-- Stop if a circular hierarchy is detected

not array_contains(components.component_id::variant, traversal.component_trace)

-- There can be some bad data that might end up in hierarchies that are artificially extremely deep

and traversal.component_hierarchy_depth < 20

),

final as (

-- Note that there may be duplicates at this point (thus "distinct").

-- Duplicates can happen when a component's parent is moved from one grandparent to another.

-- At this point, we only traced the ancestry of a component, and fixed the valid/from dates

-- so that all child ranges are contained in parent ranges.

select distinct *

from

traversal

where

-- Prevent zero-time (or less) associations from showing up

valid_from_at < valid_to_at

)

select * from final

At the end of the above step, we have a table that looks very much like the erp_components that it used as the source, but with a few additional valuable columns:

top_assembly_id- This is the most important output of the hierarchy traversal. It ties all sub components to a their common parent. We’ll use this in the next step to chop up the hierarchy into all the distinct ranges of time where the components that share a common top assembly are constant (and each distict range of time andtop_assembly_idgetting their own surrogate key).component_hierarchy_depth- Indicates how far removed a component is from the top assembly.component_trace- Contains an array of all the components linking this component to the top assembly.valid_from_at/valid_to_at- If you have really high-quality source data, these will be identical toinstalled_at/removed_at. However, in the real world, we’ve found cases where the installed and removal dates are not consistent between parent and child, either due to a data entry error or a technician forgetting to note when a component was removed. So for example, we may have a parent assembly that was removed along with all of its children, but only the parent assembly hasremoved_atpopulated. At this point, thevalid_from_atandvalid_to_attidy up these kinds of scenarios.

Temporal range join

The last step is perform a temporal range join between the top assembly and all of its descendents. This is what splits out all of the time-varying component changes into distinct ranges of time where the component hierarchy is constant. This range join makes use of the dbt macro in this gist, the operation of which is out-of-scope for this article, but you are encouraged to investigate it and the discourse post mentioned earlier.

-- Start with all of the assemblies at the top (hierarchy depth = 0)

with l0_assemblies as (

select

top_assembly_id,

component_id,

-- Prep fields required for temporal range join

{{ dbt_utils.surrogate_key(['component_id', 'valid_from_at']) }} as dbt_scd_id,

valid_from_at as dbt_valid_from,

valid_to_at as dbt_valid_to

from

component_traversal

where

component_hierarchy_depth = 0

),

components as (

select

top_assembly_id,

component_hierarchy_depth,

component_trace,

assembly_id,

component_id,

installed_at,

removed_at,

-- Prep fields required for temporal range join

{{ dbt_utils.surrogate_key(['component_trace', 'valid_from_at'])}} as dbt_scd_id,

valid_from_at as dbt_valid_from,

valid_to_at as dbt_valid_to

from

component_traversal

),

-- Perform temporal range join

{{

trange_join(

left_model='l0_assemblies',

left_fields=[

'top_assembly_id',

],

left_primary_key='top_assembly_id',

right_models={

'components': {

'fields': [

'component_hierarchy_depth',

'component_trace',

'assembly_id',

'component_id',

'installed_at',

'removed_at',

],

'left_on': 'component_id',

'right_on': 'top_assembly_id',

}

}

)

}}

select

surrogate_key,

top_assembly_id,

component_hierarchy_depth,

component_trace,

assembly_id,

component_id,

installed_at,

removed_at,

valid_from_at,

valid_to_at

from

trange_final

order by

top_assembly_id,

valid_from_at,

component_hierarchy_depth

Bonus: component swap

Before we go, let’s investigate one other interesting scenario. Suppose we have two bikes, “Bike-1” and “Bike-2”. While performing service, a technician notices that the color on the rim of “Bike-2” matches with the frame of “Bike-1” and vice-versa. Perhaps there was a mistake made during the initial assembly process? The technician decides to swap the wheels between the two bikes. The ERP system then shows that “Wheel-1” was removed from “Bike-1” on the service date and that “Wheel-1” was installed in “Bike-2” on the same date (similarly for “Wheel-2”). To reduce clutter below, we’ll ignore Frames and Tubes.

erp_components:

assembly_id |

component_id |

installed_at |

removed_at |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bike-1 | 2023-01-01 | ||

| Bike-1 | Wheel-1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-06-01 |

| Wheel-1 | Rim-1 | 2023-01-01 | |

| Wheel-1 | Tire-1 | 2023-01-01 | |

| Bike-2 | 2023-02-01 | ||

| Bike-2 | Wheel-2 | 2023-02-01 | 2023-06-01 |

| Wheel-2 | Rim-2 | 2023-02-01 | |

| Wheel-2 | Tire-2 | 2023-02-01 | |

| Bike-2 | Wheel-1 | 2023-06-01 | |

| Bike-1 | Wheel-2 | 2023-06-01 |

When this ERP data gets converted into the multivalued dimension, we get the table below. In the ERP data, only one kind of component assembly, the wheel, was removed/installed, but in the dimensional model all of the child components come along for the ride. In the table below, we see that “Bike-1” and “Bike-2” each have two distinct ranges of valid time, one prior to the wheel swap, and one after.

mdim_components:

component_sk |

top_assembly_id |

assembly_id |

component_id |

valid_from_at |

valid_to_at |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sk1 | Bike-1 | Bike-1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-06-01 | |

| sk1 | Bike-1 | Bike-1 | Wheel-1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-06-01 |

| sk1 | Bike-1 | Wheel-1 | Rim-1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-06-01 |

| sk1 | Bike-1 | Wheel-1 | Tire-1 | 2023-01-01 | 2023-06-01 |

| sk2 | Bike-1 | Bike-1 | 2023-06-01 | ||

| sk2 | Bike-1 | Bike-1 | Wheel-2 | 2023-06-01 | |

| sk2 | Bike-1 | Wheel-2 | Rim-2 | 2023-06-01 | |

| sk2 | Bike-1 | Wheel-2 | Tire-2 | 2023-06-01 | |

| sk3 | Bike-2 | Bike-2 | 2023-02-01 | 2023-06-01 | |

| sk3 | Bike-2 | Bike-2 | Wheel-2 | 2023-02-01 | 2023-06-01 |

| sk3 | Bike-2 | Wheel-2 | Rim-2 | 2023-02-01 | 2023-06-01 |

| sk3 | Bike-2 | Wheel-2 | Tire-2 | 2023-02-01 | 2023-06-01 |

| sk4 | Bike-2 | Bike-2 | 2023-06-01 | ||

| sk4 | Bike-2 | Bike-2 | Wheel-1 | 2023-06-01 | |

| sk4 | Bike-2 | Wheel-1 | Rim-1 | 2023-06-01 | |

| sk4 | Bike-2 | Wheel-1 | Tire-1 | 2023-06-01 |

Summary

In this article, we’ve explored a strategy for creating a dimensional model for ragged time-varying hierarchies. We used a simple toy system involving one or two eBikes. In the real world, there would be many more individual products, deeper hierarchies, more component attributes, and the install/removal dates would likely be captured with a timestamp component as well. The model described here works very well even in these messier real world cases.

If you have any questions or comments, please reach out to me by commenting on this post or contacting me on dbt slack (@Sterling Paramore).